The world is enjoying unprecedented levels of interconnectedness, which has brought enormous benefits, but also some negative consequences such as diseases spreading across the globe easily and more rapidly. This has been evident with the recent outbreaks of Ebola and Zika, and COVID-19 presenting perhaps the greatest global challenge of recent times.

According to the WHO, climate change is creating new health risks and acting as a “threat multiplier”. A recent study reveals that it is making existing health challenges worse: New diseases are emerging, and old one re-emerging, with both crossing geographical boundaries. It is through health research that the causative agents of Ebola, Zika and COVID-19 were identified and detected in infected people. Research also facilitated the development of protective measures, the design of treatment regimens and guidelines, and the manufacture of a range of vaccines. It is without doubt that research and innovation (R&I) will be pivotal in combating future epidemics and other disease threats.

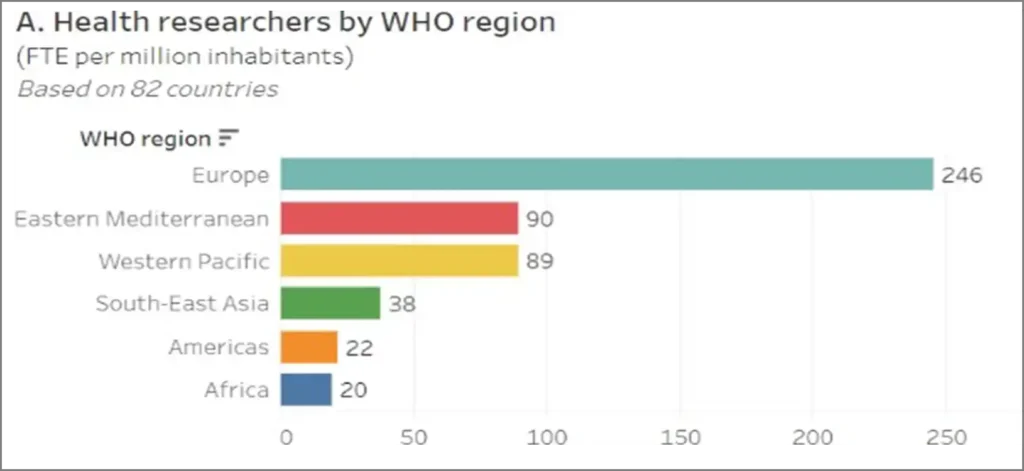

Though the importance of health research cannot be over-emphasized, research capacity has not been equitably distributed across the world. Africa lags far behind: For example, with only 20 health researchers per million people, the continent’s ratio is the lowest in the world (Europe has 246 researchers per million). While there has been improved investment in PhD training in some parts of Africa, this boosted investment has not been matched by opportunities that follow PhD completion.

Moreover, many early-career post-doctoral African researchers cannot access training for essential technical, leadership and transferrable skills that will empower them to develop their own ideas enriched by indigenous knowledge and prevailing local health needs, into compelling fundable research proposals. They also lack access to experienced mentors, research centres of excellence, research networks and international collaborative research programmes. In addition to these challenges, francophone, lusophone and other researchers who speak the plethora of different languages used on the continent must also grapple with the fact that the majority of African research published internationally is in English.

Africa has the lowest number of health researchers per capita. Image: WHO

African women research scientists also face gender inequality issues in the research arena. Gender imbalance, cultural expectations and lack of senior women to act as role models and mentors have all been identified as challenges to gender equality in African research institutions, which is affecting women researchers’ R&I output (such as publications, patents and citations). Indeed, persisting gender biases and stereotypes embedded within African research institutions create an often-challenging work environment for women scientists, who often have to juggle the responsibility of taking care of their family commitments and their careers.

The combined aforementioned challenges of a) lack of investment in post PhD training in Africa; b) lack of support structures; and c) persisting gender research inequity encourage many emerging African health researchers to abandon the profession altogether for other sources of income outside of Africa; a major cause of loss of human capital and under-utilization of the local knowledge economy. According to Daniel Hawkins Iddrisu, researcher at Cambridge University’s Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre, the current bias towards non-African research and the marginal utilization of local knowledge is perpetuating “African underdevelopment”. He adds that “the true knowledge and evidence that can guide solutions and interventions are thrown away and external solutions are borrowed and forced to fit in a totally different context”.

Following the same line of thought, Lucy Heady, CEO of Education Sub-Saharan Africa, calls for a greater focus on equitable international research partnerships and locally led research, as African researchers are best placed to meet the challenges of improving health in their countries. Their linguistic knowledge, understanding of social and cultural dynamics and appreciation of how technology can be most effectively utilized in each locale, place them at a unique vantage point of understanding the complex interplay of such dynamics.

Indeed, to address these challenges, equitable research partnerships must be prioritized at both the international level and at the local level. International equitable research partnerships, should aim to mitigate against the power imbalances that exist within the global research ecosystem and should redress the acknowledged injustice of poor research practices: i.e. “parachute” or “helicopter” research, whereby researchers from high income countries work in the Global South without the adequate involvement of or support from local researchers and infrastructure. At a local level, research equity needs to ensure greater gender equity and the inclusion of francophone and lusophone African researchers in the research arena.

Organizations such as ours, the Africa Research Excellence Fund (AREF), believe that in order to tackle the above challenges, locally led post-doctoral capacity training such as research leadership, grant writing skills workshops, mentoring, fellowship funding that supports locally led research, and capacity building that supports African research institutions are all pivotal. Supporting researchers in Africa to establish, maintain and thrive within equitable research partnerships, whether international or more local, is an underlying thread within all the professional development opportunities we provide.

Indeed, the imperative need to enhance gender equity in health research has led AREF to forge partnerships with various entities, such as the Consolidated Contractors Company (CCC) to deliver a Women Research Leadership Programme and a Grant Writing Programme specifically for women. Alongside this, a research network incorporating post-doctoral researchers throughout the continent is also emphasized, in which participants grow their networks, improve research practice, collaboration and output, and are given an equal chance at succeeding in post-doctoral research science.

Credit: Carla Rivero